The Power (and Terror) of “NO”

Strictly speaking, I’m a rookie when it comes to kids. I have a vague idea of developmental stages and what’s considered normal, but most of this comes from my education, not experience. I remember a time when my brother’s twins went through an intense ‘NO’ stage: no going to bed, no eating anything (other than mac and cheese), and no wearing shoes of any kind. Despite my adoration for these children, I remember asking myself, “Why are they being so unpleasant?” With some time and perspective, a couple of things became clear to me: 1) now that they’re pre-teens, I realize they were only getting started with unpleasantness (kidding on that one…mostly) and 2) I was mistaking disagreement with disagreeableness. This is an easy thing to do. We like people who agree with us. People who agree with us validate us and our choices. Through this common ground, they become a part of our tribe. And we tend to feel the opposite about those who apparently make it their life’s work to be diametrically opposed to us.

Judith Sills, Ph.D., wrote a great article in Psychology Today about the importance and difficulties of saying “no”. We don’t like how it makes us, and others, feel and we definitely experience the consequences associated with having less influence over the people we deny. There’s simply no getting around it. If you tell someone “no”, what are the chances of getting them to go along with you on anything else? It’s a simple matter of quid pro quo, right?

Quid Pro Quo or No?

Well yes, and no.

There is definitely a social weight associated with the give and take that affects influence. You can only rely on the kindness of others in a limited capacity if you are unable (or unwilling) to return the favor. In fact, our need to conform to group norms is so powerful that it’s a phenomenon that has been illustrated time and again. Solomon Asch’s classic 1951 study demonstrated that many people will change their views to be consistent with the group. This concept was replicated as recently as 2005 with almost identical results, but with the addition of brain scans. The results confirmed Asch’s original findings that group pressure can change a person’s perception of reality. It also demonstrated that the people who were able to resist the group felt emotional distress as a result. Though, the really unique piece about this research is the fMRI was able to show that completely different parts of the brain were involved in compliance (which engaged the perception portion) versus non-compliance (which activated an area associated with emotion).

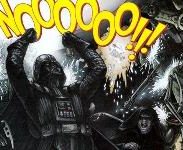

This last piece brings up an interesting idea. Saying “yes”, being agreeable, and fitting in with the group has deep roots in social behavior along with our human need to belong. The above study also indicates that there are neurobiological responses to non-compliance, or not fitting in. This is supported by another study, which found that the body releases painkillers in response to social rejection just as it would to physical injury. Apparently, the need to fit in isn’t just a matter of social structure and harmony. We all know being rejected hurts our feelings, but it is perhaps a new insight to think that humans react to rejection physically as well as emotionally. So, when my nephew was yelling, “Noooo!!” to my suggestion that adding vegetables to his steady diet of mac and cheese was a reasonable request, it made me feel bad for a number of reasons. Many of us don’t even like being rejected by strangers, which has even stronger implications for social engineering and security.

The security implications

As security professionals, we need to become comfortable with saying “no” and training our organizations to say it as well. There is obviously a practical application to common courtesy when it comes to running an efficient business with a good reputation. It is easy to lose sight of all of the consequences when it’s not a conscious decision, but instead, a possible reaction to feeling bad or awkward.

Many of you know, we’ve hosted the Social-Engineer Capture the Flag at DEF CON for the past five years. As time went on, what we’d really hoped to find is that companies were improving their defenses against inappropriate information gathering. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. The companies who have successfully shut down our contestants with a courteous, but firm denial of information have been very few and far between. What tends to happen more frequently is that information is denied out of not knowing the answer. Although pleading ignorance can be a great defense, it needs to be a conscious strategy. Security by accident isn’t really what we had in mind.

As a practitioner, are you making sure your organization is properly trained? The biggest mistake we frequently see is that many companies think that canned quarterly training on a couple of slides is sufficient to overcome human nature and bad decision making. Malicious attackers take advantage of the fact that people who hold exploitable information (HINT: that is everyone in your company) are often distracted. Individuals could also be under a lot of stress or be placed in a position to be made to feel that way.

To repeat what we’ve said in our report, security awareness training needs to be consistent, frequent, and personal. Anything else leaves you vulnerable. We learn to say “no” when we’re starting to assert our independence as human beings. Then, along the way, we learn what’s “nice” and what it takes to be included in the comfort of the tribe. People need to have it reinforced that not only is it okay to say “no”, it is often the wisest choice. We hope you think on this when planning your next training. Stay safe until then.

Written by: Michele Fincher

Sources:

https://www.social-engineer.com/validation-social-engineering-tool/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/articles/201311/the-power-no

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1952-00803-001

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15978553

https://www.nature.com/articles/mp201396

https://www.social-engineer.org/sevillage-def-con/the-sectf/

Comments are closed.