Spies and Espionage

Espionage, commonly known as spying, is the practice of secretly gathering information about a foreign government or a competing industry, with the objective of placing one’s own government or corporation at a strategic or financial advantage. However, espionage is not synonymous with all intelligence-gathering disciplines. Codebreaking (cryptanalysis or COMINT), aircraft or satellite photography, (IMINT) and open publications research (OSINT) are intelligence gathering disciplines. However, they are not considered espionage. MI5’s official website comments on the shifting focus of espionage. In the past, the focus of espionage was typically on obtaining political and military intelligence. With the increase in technology the focus has broadened to include such things as communications technologies and IT. As well as, energy, scientific research, aviation and other fields. The following examples of military and industrial spies and espionage illustrate how using influence tactics led to the successful implementation of social engineering attacks.

Spies and Espionage—State Sponsored Facebook Fakes

In January 2017 the Israeli Defense Forces published a blog on their website describing an attack on their soldiers and it’s all about the influence tactic known as liking. The attackers (reportedly Hamas operatives) created fake Facebook profiles of attractive young women. The goal of these Facebook fakes was to entices Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers to befriend them. The Facebook fakes built trust and rapport through messaging and photo sharing. Then the operative (spies) would inquire if the soldier would like to video chat. To do so, requires installing an app that is actually a virus. Once installed the soldiers’ mobile device becomes an open book. Contacts, location, apps, pictures, and files are all now accessible to Hamas operatives.

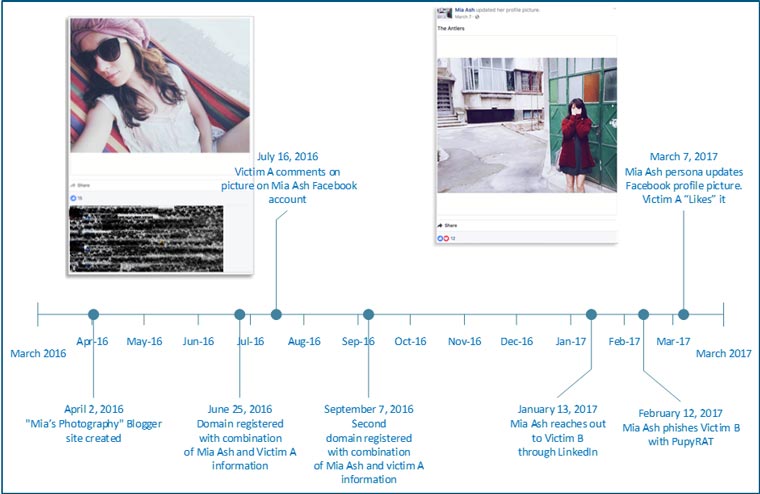

Cobalt Gypsy aka OilRig, Create ‘Mia Ash’—Spies and Espionage

In early 2017 Secureworks unearthed a years-long campaign of espionage and possibly data destruction all centered around a pretty, but fake, photographer named ‘Mia Ash’. The ‘Mia Ash’ persona had active accounts on LinkedIn, Facebook, Blogger and WhatsApp. Once again, the influence tactic of liking is seen in this espionage campaign. After building rapport and trust through messaging and photo sharing, ‘Mia Ash’ would send a ‘photography survey’ to ‘her’ target. Usually a middle age man in the telecommunications, government, defense, oil, or finance industry. The ‘photography survey’ in reality was an attachment with concealed malware. The malware gave ‘Mia Ash’ complete control to the compromised computer with access to network credentials.

Fancy Bear aka APT 28 Spear Phishing Attacks Breach Podesta, Powell, and the DNC

The 2016 US presidential election saw spear phishing attacks targeting high profile members of government. On March 19, 2016, Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman John Podesta, received an alarming email that appeared to come from Google informing him that someone had used his password to try to access his Google account. The phishing email included a link to a spoofed Google webpage informing him to change his password. Mr. Podesta clicked the link and changed his password, or so he thought. Instead, he gave his Google password to Fancy Bear, a Russian state-sponsored cyber espionage group.

Bronze Butler or Tick Suspected of Stealing IP From Japanese Enterprises

The attackers known as Bronze Butler and Tick continue to use spear phishing and watering holes to breach intellectual property. As reported on October 12, 2017 by Secureworks, the targets selected are related to technology and development, business and sales information, emails and meeting schedules, product specifications, and network and system configuration file.

The report does not include the specifics of the spear phishing emails. However the very nature of a spear phish implies that the attackers have spent time conducting OSINT. Using influence tactics such as authority, obligation, reciprocity the attackers can craft an email that caters to the recipient’s job, personal situation or preferences. For example, the email may claim to come from a company you do business with. For example, your bank, or the internet company you use like Google. Because spear phishing emails leverage a certain level of information about an individual they can be very difficult to detect or resist.

The Takeaway

- Be security conscious when it comes to information you make public on any social media platform. As reported by naked security all IDF soldiers targeted by Hamas in the ‘Facebook Fake’ attack were found through public photos with tags and posts revealing they were active in IDF military service.

- The use of social media by Cobalt Gypsy and spear phishing by Bronze Butler highlights the importance of ongoing social engineering training. Clear guidelines for social media usage, as well as education or identifying potential phishing lures are essential for employees. Clear company policies should be in place for reporting potential phishing messages received through corporate/personal email, and social media platforms.

For a discussion on this topic see Podcast Episode 95, Pretext, Spying and Espionage.